- Home

- Bogi Takács

Transcendent 2 Page 2

Transcendent 2 Read online

Page 2

What did it mean to be a real authentic person, in an era when everything great from the past was twenty feet underwater? Would you embrace prefab newness, or try to copy the images you can see from the handful of docs we’d scrounged from the Dataclysm? When we got tired of playing music, an hour before dawn, we would sit around arguing, and inevitably you got to that moment where you were looking straight into someone else’s eyes and arguing about the past, and whether the past could ever be on land, or the past was doomed to be deep underwater forever.

I felt like I was just drunk all the time, on that cheap-ass vodka that everybody chugged in Fairbanks, or maybe on nitrous. My head was evaporating, but my heart just got more and more solid. I woke up every day on my bunk, or sometimes tangled up in someone else’s arms and legs on the daybed, and felt actually jazzed to get up and go clean the scrubbers or churn the mycoprotein vats.

Every time we put down the bridge to the big island and turned off our moat, I felt everything go sour inside me, and my heart went funnel-shaped. People sometimes just wandered away from the Wrong Headed community without much in the way of goodbye—that was how Juya had gone—but meanwhile, new people showed up and got the exact same welcome that everyone had given to me. I got freaked out thinking of my perfect home being overrun by new selfish loud fuckers. Joconda had to sit me down, at the big table where sie did all the official business, and tell me to get over myself because change was the ocean and we lived on her mercy. “Seriously, Pris. I ever see that look on your face, I’m going to throw you into the myco vat myself.” Joconda stared at me until I started laughing and promised to get with the program.

And then one day I was sitting at our big table, overlooking the straits between us and the big island. Staring at Sutro Tower and the tops of the skyscrapers poking out of the water here and there. And this obnoxious skinny bitch sat down next to me, chewing in my ear and talking about the impudence of impermanence or some similar. “Miranda,” she introduced herself. “I just came up from Anaheim-Diego. Jeez, what a mess. They actually think they can build nanomechs and make it scalable. Whatta bunch of poutines.”

“Stop chewing in my ear,” I muttered. But then I found myself following her around everywhere she went.

Miranda was the one who convinced me to dive into the chasm of Fillmore Street in search of a souvenir from the old Church of John Coltrane, as a present for Joconda. I strapped on some goggles and a big apparatus that fed me oxygen while also helping me to navigate a little bit, and then we went out in a dinghy that looked old enough that someone had actually used it for fishing. Miranda gave me one of her crooked grins and studied a wrinkled old map. “I thinnnnnk it’s right around here.” She laughed. “Either that or the Korean barbecue restaurant where the mayor got assassinated that one time. Not super clear which is which.”

I gave her a murderous look and jumped into the water, letting myself fall into the street at the speed of water resistance. Those sunken buildings turned into doorways and windows facing me, but they stayed blurry as the bilge flowed around them. I could barely find my feet, let alone identify a building on sight. One of these places had been a restaurant, I was pretty sure. Ancient automobiles lurched back and forth, like maybe even their brakes had rusted away. I figured the Church of John Coltrane would have a spire like a saxophone? Maybe? But all of the buildings looked exactly the same. I stumbled down the street, until I saw something that looked like a church, but it was a caved-in old McDonald’s restaurant. Then I tripped over something, a downed pole or whatever, and my face mask cracked as I went down. The water was going down my throat, tasting like dirt, and my vision went all pale and wavy.

I almost just went under, but then I thought I could see a light up there, way above the street, and I kicked. I kicked and chopped and made myself float. I churned up there until I broke the surface. My arms were thrashing above the water and then I started to go back down, but Miranda had my neck and one shoulder. She hauled me up and out of the water and threw me into the dinghy. I was gasping and heaving up water, and she just sat and laughed at me.

“You managed to scavenge something after all.” She pointed to something I’d clutched at on my way up out of the water: a rusted, barbed old piece of a car. “I’m sure Joconda will love it.”

“Ugh,” I said. “Fuck Old San Francisco. It’s gross and corroded and there’s nothing left of whatever used to be cool. But hey. I’m glad I found a group of people I would risk drowning in dead water for.”

4. I chose to see that as a special status

Miranda had the kind of long-limbed, snaggle-toothed beauty that made you think she was born to make trouble. She loved to roughhouse, and usually ended up with her elbow on the back of my neck as she pushed me onto the dry dirt. She loved to invent cute insulting nicknames for me, like “Dollypris” or “Pris Ridiculous.” She never got tired of reminding me that I might be a ninth level genderfreak, but I had all kinds of privilege, because I grew up in Fairbanks and never had to wonder how we were going to eat.

Miranda had this way of making me laugh even when the news got scary, when the government back in Fairbanks was trying to reestablish control over the whole West Coast, and extinction rose up like the shadows at the bottom of the sea. I would start to feel that scab inside my stomach, like the whole ugly unforgiving world could come down on us and our tiny island sanctuary at any moment, Miranda would suddenly start making up a weird dance or inventing a motto for a team of superhero mosquitos, and then I would be laughing so hard it was like I was squeezing the fear out of my insides. Her hands were a mass of scar tissue but they were as gentle as dried-up blades of grass on my thighs.

Miranda had five other lovers, but I was the only one she made fun of. I chose to see that as a special status.

5. “What are you people even about”

Falling in love with a community is always going to be more real that any love for a single human being could ever be. People will let you down, shatter your image of them, or try to melt down the wall between your self-image and theirs. People, one at a time, are too messy. Miranda was my hero and the lover I’d pretty much dreamed of since both puberties, but I also saved pieces of my heart for a bunch of other Wrong Headed people. I loved Joconda’s totally random inspirations and perversions, like all of the art projects sie started getting me to build out of scraps from the sunken city after I brought back that car piece from Fillmore Street. Zell was this hyperactive kid with wild half-braids, who had this whole theory about digging up buried hard drives full of music files from the digital age, so we could reconstruct the actual sounds of Marvin Gaye and the Jenga Priests. Weo used to sit with me and watch the sunset going down over the islands, we didn’t talk a lot except that Weo would suddenly whisper some weird beautiful notion about what it would be like to live at sea, one day when the sea was alive again. But it wasn’t any individual, it was the whole group, we had gotten in a rhythm together and we all believed the same stuff. The love of the ocean, and her resilience in the face of whatever we had done to her, and the power of silliness to make you believe in abundance again. Openness, and a kind of generosity that is the opposite of monogamy.

But then one day I looked up, and some of the faces were different again. A few of my favorite people in the community had bugged out without saying anything, and one or two of the newcomers started seriously getting on my nerves. One person, Mage, just had a nasty temper, going off at anyone who crossed hir path whenever xie was in one of those moods, and you could usually tell from the unruly condition of Mage’s bleach-blond hair and the broke-toothed scowl. Mage became one of Miranda’s lovers right off the bat, of course.

I was just sitting on my hands and biting my tongue, reminding myself that I always hated change and then I always got used to it after a little while. This would be fine: change was the ocean and she took care of us.

Then we discovered the spoilage. We had been filtering the ocean water, removing toxic waste, filtering out exc

ess gunk, and putting some of the organic byproducts into our mycoprotein vats as a feedstock. But one day, we opened the biggest vat and the stench was so powerful we all started to cry and retch, and we kept crying even after the puking stopped. Shit, that was half our food supply. It looked like our whole filtration system was off, there were remnants of buckystructures in the residue that we’d been feeding to our fungus, and the fungus was choking on them. Even the fungus that wasn’t spoiled would have minimal protein yield. And this also meant that our filtration system wasn’t doing anything to help clean the ocean, at all, because it was still letting the dead pieces of buckycrap through.

Joconda just stared at the mess and finally shook hir head and told us to bury it under the big hillside.

We didn’t have enough food for the winter after that, so a bunch of us had to make the trip up north to Marin, by boat and on foot, to barter with some gun-crazy farmers in the hills. And they wanted free labor in exchange for food, so we left Weo and a few others behind to work in their fields. Trudging back down the hill pulling the first batch of produce in a cart, I kept looking over my shoulder to see our friends staring after us, as we left them surrounded by old dudes with rifles.

I couldn’t look at the community the same way after that. Joconda fell into a depression that made hir unable to speak or look anyone in the eye for days at a time, and we were all staring at the walls of our poorly repaired dormitory buildings, which looked as though a strong wind could bring them down. I kept remembering myself walking away from those farmers, the way I told Weo it would be fine, we’d be back before anyone knew anything, this would be a funny story later. I tried to imagine myself doing something different. Putting my foot down maybe, or saying fuck this, we don’t leave our own behind. It didn’t seem like something I would ever do, though. I had always been someone who went along with what everybody else wanted. My one big act of rebellion was coming here to Bernal Island, and I wouldn’t have ever come if Juya hadn’t already been coming.

Miranda saw me coming and walked the other way. That happened a couple of times. She and I were supposed to have a fancy evening together, I was going to give her a bath even if it used up half my water allowance, but she canceled. We were on a tiny island but I kept only seeing her off in the distance, in a group of others, but whenever I got closer she was gone. At last I saw her walking on the big hill, and I followed her up there, until we were almost at eye level with the Transamerica Pyramid coming up out of the flat water. She turned and grabbed at the collar of my shirt and part of my collarbone. “You gotta let me have my day,” she hissed. “You can’t be in my face all the time. Giving me that look. You need to get out of my face.”

“You blame me,” I said, “for Weo and the others. For what happened.”

“I blame you for being a clingy wet blanket. Just leave me alone for a while. Jeez.” And then I kept walking behind her, and she turned and either made a gesture that connected with my chest, or else intentionally shoved me. I fell on my butt. I nearly tumbled head over heels down the rocky slope into the water, but then I got a handhold on a dead root.

“Oh fuck. Are you okay?” Miranda reached down to help me up, but I shook her off. I trudged down the hill alone.

I kept replaying that moment in my head, when I wasn’t replaying the moment when I walked away with a ton of food and left Weo and the others at gunpoint. I had thought that being here, on this island, meant that the only past that mattered was the grand, mysterious, rebellious history that was down there under the water, in the wreckage of San Francisco. All of the wild music submerged between its walls. I had thought my own personal past no longer mattered at all. Until suddenly, I had no mental energy for anything but replaying those two memories. Uglier each time around.

And then someone came up to me at lunch, as I sat and ate some of the proceeds from Weo’s indenture: Kris, or Jamie, I forget which. And he whispered, “I’m on your side.” A few other people said the same thing later that day. They had my back, Miranda was a bitch, she had assaulted me. I saw other people hanging around Miranda and staring at me, talking in her ear, telling her that I was a problem and they were with her.

I felt like crying, except that I couldn’t find enough moisture inside me. I didn’t know what to say to the people who were on my side. I was too scared to speak. I wished Joconda would wake up and tell everybody to quit it, to just get back to work and play and stop fomenting.

The next day, I went to the dining area, sitting at the other end of the long table from Miranda and her group of supporters. Miranda stood up so fast she knocked her own food on the floor, and she shouted at Yozni, “Just leave me the fuck alone. I don’t want you on ‘my side,’ or anybody else. There are no sides. This is none of your business. You people. You goddamn people. What are you people even about?” She got up and left, kicking the wall on her way out.

After that, everybody was on my side.

6. The honeymoon was over, but the marriage was just starting

I rediscovered social media. I’d let my friendships with people back in Fairbanks and elsewhere run to seed, during all of this weird, but now I reconnected with people I hadn’t talked to in a year or so. Everybody kept saying that Olympia had gotten really cool since I left, there was a vibrant music scene now and people were publishing zootbooks and having storytelling slams and stuff. And meanwhile, the government in Fairbanks had decided to cool it on trying to make the coast fall into line, though there was talk about some kind of loose articles of confederation at some point. Meanwhile, we’d even made some serious inroads against the warlords of Nevada.

I started looking around the dormitory buildings and kitchens and communal playspaces of Bernal, and at our ocean reclamation machines, as if I was trying to commit them to memory. One minute, I was looking at all of it as if this could be the last time I would see any of it, but then the next minute, I was just making peace with it so I could stay forever. I could just imagine how this moment could be the beginning of a new, more mature relationship with the Wrong Headed crew, where I wouldn’t have any more illusions, but that would make my commitment even stronger.

I sat with Joconda and a few others, on that same stretch of shore where we’d all stood naked and launched candles, and we held hands after a while. Joconda smiled, and I felt like sie was coming back to us, so it was like the heart of our community was restored. “Decay is part of the process. Decay keeps the ocean warm.” Today Joconda had wild hair with some bright colors in it, and a single strand of beard. I nodded.

Instead of the guilt or fear or selfish anxiety that I had been so aware of having inside me, I felt a weird feeling of acceptance. We were strong. We would get through this. We were Wrong Headed.

I went out in a dinghy and sailed around the big island, went up towards the ruins of Telegraph. I sailed right past the Newsom Spire, watching its carbon-fiber cladding flake away like shiny confetti. The water looked so opaque, it was like sailing on milk. I sat there in the middle of the city, a few miles from anyone, and felt totally peaceful. I had a kick of guilt at being so selfish, going off on my own when the others could probably use another pair of hands. But then I decided it was okay. I needed this time to myself. It would make me a better member of the community.

When I got back to Bernal, I felt calmer than I had in ages, and I was able to look at all the others—even Mage, who still gave me the murder eye from time to time—with patience and love. They were all my people. I was lucky to be among them.

I had this beautiful moment, that night, standing by a big bonfire with the rest of the crew, half of us some level of naked, and everybody looked radiant and free. I started to hum to myself, and it turned into a song, one of the old songs that Zell had supposedly brought back from digital extinction. It had this chorus about the wild kids and the wardance, and a bridge that doubled back on itself, and I had this feeling, like maybe the honeymoon is over, but the marriage is just beginning.

Then I found my

self next to Miranda, who kicked at some embers with her boot. “I’m glad things calmed down,” I whispered. “I didn’t mean for everyone to get so crazy. We were all just on edge, and it was a bad time.”

“Huh,” Miranda said. “I noticed that you never told your peeps to cool it, even after I told the people defending me to shut their faces.”

“Oh,” I said. “But I actually,” and then I didn’t know what to say. I felt the feeling of helplessness, trapped in the grip of the past, coming back again. “I mean, I tried. I’m really sorry.”

“Whatever,” Miranda said. “I’m leaving soon. Probably going back to Anaheim-Diego. I heard they made some progress with the nanomechs after all.”

“Oh.” I looked into the fire, until my retinas were all blotchy. “I’ll miss you.”

“Whatever.” Miranda slipped away. I tried to mourn her going, but then I realized I was just relieved. I wasn’t going to be able to deal with her hanging around, like a bruise, when I was trying to move forward. With Miranda gone, I could maybe get back to feeling happy here.

Joconda came along when we went back up into Marin to get the rest of the food from those farmers, and collect Weo and the two others we had left there. We climbed up the steep path from the water, and Joconda kept needing to rest. Close to the water, everything was the kind of salty and moist that I’d gotten used to, but after a few miles, everything got dry and dusty. By the time we got to the farm, we were thirsty and we’d used up all our water, and the farmers saw us coming and got their rifles out.

Our friends had run away, the farmers said. Weo and the others. A few weeks earlier, and they didn’t know where. They just ran off, left the work half done. So, too bad, we weren’t going to get all the food we had been promised. Nothing personal, the lead farmer said. He had sunburnt cheeks, even though he wore a big straw hat. I watched Joconda’s face pass through shock, anger, misery and resignation, without a single word coming out. The farmers had their guns slung over their shoulders, enough of a threat without even needing to aim. We took the cart, half full of food instead of all the way full, back down the hill to our boat.

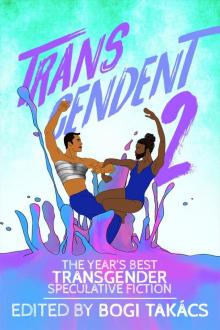

Transcendent 2

Transcendent 2