- Home

- Bogi Takács

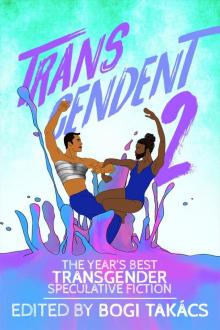

Transcendent 2 Page 3

Transcendent 2 Read online

Page 3

We never found out what actually happened to Weo and the others.

7. “That’s such an inappropriate line of inquiry

I don’t even know how to deal”

I spent a few weeks pretending I was in it for the long haul on Bernal Island, after we got back from Marin. This was my home, I had formed an identity here that meant the world to me, and these people were my family. Of course I was staying.

Then one day, I realized I was just trying to make up my mind whether to go back to Olympia, or all the way back to Fairbanks. In Fairbanks, they knew how to make thick-cut toast with egg smeared across it, you could go out dancing in half a dozen different speakeasies that stayed open until dawn. I missed being in a real city, kind of. I realized I’d already decided to leave San Francisco a while ago, without ever consciously making the decision.

Everyone I had ever had a crush on, I had hooked up with already. Some of them, I still hooked up with sometimes, but it was nostalgia sex rather than anything else. I was actually happier sleeping alone, I didn’t want anybody else’s knees cramping my thighs in the middle of the night. I couldn’t forgive the people who sided with Miranda against me, and I was even less able to forgive the people who sided with me against Miranda. I didn’t like to dwell on stuff, but there were a lot of people I had obscure, unspoken grudges against, all around me. And then occasionally I would stand in a spot where I’d watched Weo sit and build a tiny raft out of sticks, and would feel the anger rise up all over again. At myself, mostly.

I wondered about what Miranda was doing now, and whether we would ever be able to face each other again. I had been so happy to see her go, but now I couldn’t stop thinking about her.

The only time I even wondered about my decision was when I looked at the ocean, and the traces of the dead city underneath it, the amazing heritage that we were carrying on here. Sometimes I stared into the waves for hours, trying to hear the sound waves trapped in them, but then I started to feel like maybe the ocean had told me everything it was ever going to. The ocean always sang the same notes, it always passed over the same streets and came back with the same sad laughter. And staring down at the ocean only reminded me of how we’d thought we could help to heal her, with our enzyme treatments, a little at a time. I couldn’t see why I had ever believed in that fairy tale. The ocean was going to heal on her own, sooner or later, but in the meantime we were just giving her meaningless therapy that made us feel better more than it actually helped. I got up every day and did my chores. I helped to repair the walls and tend the gardens and stuff. But I felt like I was just turning wheels to keep a giant machine going, so that I would be able to keep turning the wheels tomorrow.

I looked down at my own body, at the loose kelp-and-hemp garments I’d started wearing since I’d moved here. I looked at my hands and forearms, which were thicker, callused, and more veiny with all the hard work I’d been doing here—but also, the thousands of rhinestones in my fingernails glittered in the sunlight, and I felt like I moved differently than I used to. Even with all everything shitty that had happened, I’d learned something here, and wherever I went from now on, I would always be Wrong Headed.

I left without saying anything to anybody, the same way everyone else had.

A few years later, I had drinks with Miranda on that new floating platform that hovered over the wasteland of North America. Somehow we floated half a mile above the desert and the mountaintops—don’t ask me how, but it was carbon neutral and all that good stuff. From up here, the hundreds of miles of parched earth looked like piles of gold.

“It’s funny, right?” Miranda seemed to have guessed what I was thinking. “All that time, we were going on about the ocean and how it was our lover and our history and all that jazz. But look at that desert down there. It’s all beautiful, too. It’s another wounded environment, sure, but it’s also a lovely fragment of the past. People sweated and died for that land, and maybe one day it’ll come back. You know?” Miranda was, I guess, in her early thirties, and she looked amazing. She’d gotten the snaggle taken out of her teeth, and her hair was a perfect wave. She wore a crisp suit and she seemed powerful and relaxed. She’d become an important person in the world of nanomechs.

I stopped staring at Miranda and looked over the railing, down at the dunes. We’d made some pretty major progress at rooting out the warlords, but still nobody wanted to live there, in the vast majority of the continent. The desert was beautiful from up here, but maybe not so much up close.

“I heard Joconda killed hirself,” Miranda said. “A while ago. Not because of anything in particular that had happened. Just the depression, it caught up with hir.” She shook her head. “God. Sie was such an amazing leader. But hey, the Wrong Headed community is twice the size it was when you and I lived there, and they expanded onto the big island. I even heard they got a seat at the table of the confederation talks. Sucks that Joconda won’t see what sie built get that recognition.”

I was still dressed like a Wrong Headed person, even after a few years. I had the loose flowy garments, the smudgy paint on my face that helped obscure my gender rather than serving as a guide to it, the straight-line thin eyebrows and sparkly earrings and nails. I hadn’t lived on Bernal in years, but it was still a huge part of who I was. Miranda looked like this whole other person, and I didn’t know whether to feel ashamed that I hadn’t moved on, or contemptuous of her for selling out, or some combination. I didn’t know anybody who dressed the way Miranda was dressed, because I was still in Olympia where we were being radical artists.

I wanted to say something. An apology, or something sentimental about the amazing time we had shared, or I don’t even know what. I didn’t actually know what I wanted to say, and I had no words to put it into. So after a while I just raised my glass and we toasted to Wrong Headedness. Miranda laughed, that same old wild laugh, as our glasses touched. Then we went back to staring down at the wasteland, trying to imagine how many generations it would take before something green came out of it.

Thanks to Burrito Justice for the map, and Terry Johnson for the biotech insight

Skerry-Bride

• Sonya Taaffe •

You love a jötunn. You have never grown used to the cold. Of such contradictions are the loves of Midgard made.

Dröfn this time is a woman dressed like a hunter, as if to recall Skaði who married once across the worlds, but her hair roped down her back is as heavy and powerful as a wave breaking by night, black curling over the deepest green. It is not her sea-nature giving itself away; she has come before with hair as red as blood on wreck-foam, russet as late apples, blue as anime, any more than the winter whiteness of her skin is a tell of the chill running in her veins like a stream so deep beneath its lock of ice, to break through in hopes of touching live water is to tumble at once, and be trapped, and drown, screaming glassily as a sailor in the ship-breaking arms of the sea. She has been warm to the touch, summer-tanned as toast. She has been a man with skin as brown as ash-bark, gently mocking, and she has been neither, crackling in your arms like a lace of ice and birch twigs, the low wind-bent sedge and the bitter salt of black-cragged shores. (She has tasted of wood-moss and the musk of arctic foxes, lain a grey seal’s furnace heat against your belly. She has slicked your fingers with the weed-tanglings of dabberlocks and oarweed. You know nights of nothing human, nothing that even breathes. Your sheets have smelled of peat mist in the morning.) She leans against your doorframe in old soft jeans stained at the knees with leaf-mold and a shirt in pheasant-colored plaid, autumnal as the leather of the flying jacket she shrugged off, coming indoors, and it is not her true look, any more than the true color of her eyes is the blue-black you see more often than not, licking like frostbite at your flesh; she is a stranger and you open the door to her every time, knowing someday there will be nothing to recognize.

You knew from the first, when a man with the wind-tightened face of a traveler and hair as pale as the drifting limbs of drowned men call

ed you by the name you had not told him and you were not, instantly, afraid. It was summer then and he looked cool enough to lay like a nurse’s wrist against your forehead, ice just melting to press against your lips. His bones were not boulders, he had only the usual number of heads; you saw two movies and a concert together, argued about representation in popular culture and ransacked your liquor cabinet for an experiment in obsolete cocktails, and when you woke that first morning beside a round-chinned woman whose hair coiled down between your skins as slipperily as shoreweed, it was no surprise. You did not try to guess her name, like a kenning riddle; she gave it before she left, quick as a flick of spray or the shiver-making skim of her mouth against yours one last time before she pulled on the T-shirt she had not been wearing last night and disappeared before she had even crossed the street. Only in the shower did you find the marks like port-wine spills or the press of great heat or cold, coming out under the slither of soap and water wherever his hands, hers, had rested for more than a moment on hip, shoulder, thigh, throat. They faded within the day, flared up tingling like pins and needles when a sharp-wristed girl with bilberries crushed around her mouth rapped two weeks later on the window where only oak leaves in their late-curling green had tossed a moment before. It is not an infallible sign. She has surprised you—squirrel, busker, shadow at the edge of the streetlight—before.

She will drown you, perhaps, one day, although you have never read that Ægir’s daughters were sirens. You carry a gold coin in your pocket for her mother just in case, bought from the antique shop where the two of you lingered one afternoon over fin-de-siècle inkwells and memoirs of the merchant marine. She does not speak of Ragnarök or the Æsir, of Jötunheimr if she misses it or her father’s cauldron-brewing hall, hung with the skins of sea-monsters and the nets of Rán. You joke about backpacking around Iceland or Norway, but not with your job as poor as it is, not with the strange nagging fear that Dröfn among her sisters might be something even less easily loved than the shape-changer she is now. Her kind are frost and fire and you cannot hold her safely or for long, no matter the shape she assumes to feel it. Your breath flashes white from kissing her, your fingers inside her ache like winter iron; she moves within you like a frozen sea, whitecaps above and the breathless abyss below. He lies afterward with his head in the hollow of your shoulder, winding the places over your still-trembling skin where his tattoos would twine like the bow of a dragon ship. When you begin to unbutton her hunter’s shirt, the weight of her wave-rolling hair will blind you.

You touch her cheek, stark-boned as the failing season; you breathe her scent, this time of trampled rowan and rime. You watch her eyes shift color, the storm-light of St. Elmo’s fire playing about church spires and mast-tops. You do not ask if she loves you, because she returns, any more that you tell her she does not, because she never returns the same. She leans into your touch, your warmth, everything she might be holding still for you; she is the stranger you know best and you draw the door shut behind her, this time as every other. You know what is true.

Transitions

• Gwen Benaway •

I am late. Crossing subway lines, zigzagging through the city’s underground, takes more time than I have. My Blackberry blinks red with twenty-five unread messages from work. My second phone, the one which links me to my other life, is also blinking with unread notifications. There is nothing for it but to rush to my appointment and hope there isn’t anything urgent to deal with when I return to the office.

I push into the final train which will take me to the row of medical buildings and hospitals perched along University Avenue. All the seats are taken so I grab one of the metal poles near the door and hold on. I see my face in the train glass, highlighted by the reflected lights of the subway tunnel. My foundation is too heavy. I look whiter than usual, a combination of my half-breed skin tone and the mattifying powder I use to set my face. Half of transitioning from a man to a woman is learning to blend. The other half is hair removal.

I finished the first stage of my transition last fall. Now I’m working on the second stage, hormones and living full time as my chosen gender. This is why I’m heading to University Avenue in the middle of my work week, frantic and looking like a transgender ghost. They are running a new drug study on hormone therapy and need transgender guinea pigs. I signed up because they promised fewer side effects, lower cancer risks, and ongoing medical monitoring. I already have a doctor in the overworked clinic in the Village but since more support is better than less, I volunteered.

The train lurches every time it reaches a stop, pushing me off balance on my heels and forcing me to grip tighter onto the railing. I feel the glances from my fellow riders. Some days, in low light and when I’ve had time to work at it, I can pass if I don’t speak. On days like today, behind schedule and plastering my foundation on between cups of coffee at work, I’m an obvious transwoman. I tell myself I don’t care what people think. If looking like a supermodel was my primary motivation for transitioning, I’d have backed out after the first painful electrolysis session.

A man on the right side of the train keeps looking at my face. He is caught between fascination and disgust. He stares at my face, drops his eyes over my body like appraising artwork, and then looks back at my face again. I know the look. It means he thinks I’m a man but he isn’t sure. He is searching me for some sign to confirm whatever assumptions he has created in his mind. I keep my eyes averted, focusing on the narrow billboards running along the top of the train. Let him think what he wants. I’m too late to care.

People think hormones are a magic pill which transform you into Tyra Banks. It doesn’t work like that. They can soften your skin, shift your fat storage, but at the end of day, it’s makeup and lasers which help you pass as a woman. Not that passing is my goal, but it makes you safer in public if no one can tell. I’d like to walk out of my condo and not feel like I was going to end up on the news for wearing my favourite dress, the one which shows off my arms and pushes up my tits like a platter of heaven. So here I am, departing the train at Museum station in downtown Toronto, heading into a research laboratory connected to Mount Sinai Hospital. Praying they haven’t cancelled my appointment and don’t put me into the control group that get a sugar pill. I need estrogen like a desert caravan needs a well.

Somehow I navigate the building maze and end up in the waiting room two minutes before my appointment is scheduled to begin. The letter they mailed me along with my legal waiver said to be fifteen minutes early, but the bored admin just waves me into one of the offices behind her desk and tells me to fill out my intake forms when my meeting with the research lead is done. I walk into the office, feeling like a shaved mouse about to be injected with bladder-cancer cells. It looks like every office on TV, beige and cluttered with file folders and sad spider plants.

The research lead is a polite woman in her late forties. Her glasses are heavy purple resin, suggesting a glamorous artistic personality. Her brown cashmere sweater, crumb laden and smudged with makeup, suggests a life of PBS documentaries and CBC Radio 1 interviews. The contrast is striking. As she leads me through a series of questions about my gender history, I find myself cataloguing the various inconsistencies in her appearance. Sensible flat black shoes imply a practical nature. A photo next to her desktop computer shows her in a tropical location with an oversized margarita and a leopard-print bikini. I wonder if she has an undisclosed drinking problem, one which encouraged her to pick out the glasses and buy the swimsuit when her real personality was safely saturated into incoherence.

My friends would tell me my focus on her appearance is patriarchy in action. I imagine my non-binary friend, Sten, scolding me by saying “women judging other women is how men police our bodies when they aren’t present.” I agree, but in this moment, listening to her list the long line of possible effects and downstream impacts to my biology, picking out the most banal parts of the interaction is the only way I can keep my skinny latte down. When I first came out of

the Trans closet, announced my transition, and started the long process of hair removal, I felt an immediate and persistent urge to vomit. I feel the same rush of energy to my stomach now.

I interrupt, coughing to push down the bile in my throat. “Look, I know about the risks. I’ve read the forms and research.” This wasn’t lying, because I had used my workplace subscription to Pubmed to scour all research related to hormone therapy from the last twenty years. “Can I just sign whatever I need to sign and start?”

She blinks at me once, mentally turning off her script and moving back to real conversation. “Yes, I’m sure you have.” She pauses to purse her lips and pushes her glasses up higher on her nose. “But there are unique risks with this drug. Its bioavailability is much higher than older treatments. We’re not sure how it will work in human trials.”

I resist the urge to roll my eyes. I smile, tight around the corners. “Sure, but the study was approved which means it’s been reviewed and the animal trials had a tolerable side-effect profile. So please, if we can move on, I’d appreciate it.”

She shrugs and spreads her hands. “Fine. Just stick to the dosing schedule and make sure you don’t miss any of your blood-work appointments.” She passes me a legal waiver to initial and date. I sign it. She files it into a blue folder and passes me another form to sign, this one confirming we went through the risks and she answered any questions I might have. I sign it as well.

Transcendent 2

Transcendent 2